On October 1 at 3 a.m. in Avignon, France, I lay awake in a hotel room feeling sick to my core for Western North Carolina, a part of the country I feel a deep pull to and have visited frequently for twenty-odd years. The city and surrounds of Asheville, specifically, but the entirety of the Southern Appalachians calls to me. The Blue Ridge Mountains fill me with peace, make me feel both held and lifted. It’s not unlikely that some of my ancestors lived there, and my husband’s father’s people are from WNC. The progressive, arts-driven culture of Asheville, plus its mountain landscape, is 100% my vibe, the precise kind of place I want to invest my money and live out my days. I have old friends who live in the region. We’ve daydreamed about us moving there someday. (Which feels a bit cliché; a lot of people have that idea. But still.) We’ve visited at least annually Thalia’s entire life, for a yearly gathering with my in-laws and Thalia’s cousins. Core memories were made, photos were taken, etc. Thalia and I have taken two mother-daughter road trips there.

Asheville has been, for all of us, a special place, a place of delight and respite, a kind of haven. Unsurprisingly, Thalia loves it like Todd and I do, and because of that love, she’s had UNC-Asheville at the top of her college prospects list.

In France, I lay awake and scrolled through images of the ruined River Arts District and destroyed mountain roads and homes, and suggestions of where best to donate aid. I knew that it didn’t matter if I were back home in East Nashville, 4615 miles closer to Hurricane Helene’s impact, or in an ancient village in Provence: Either way, the best I could do to help would be to Venmo money and share information, both of which I did.

What I couldn’t do was fully lower myself into a muck of grief and sorrow about what I saw happening. I couldn’t read or focus enough on the news about Hurricane Helene’s aftermath. Which is to say I was sheltered, in France, from a degree of emotional pain that I would have succumbed to readily were I at home.

It wasn’t just that I was on vacation, a privileged space one allows oneself to enter if one is, well, privileged enough to do so; or that I was tasked with navigating a foreign country where I only speak only a rudimentary level of the language. I also had the responsibility to project enthusiasm and inspiration to my fellow travelers, a group of women who were there to write with me and each other. It would have been professionally inappropriate of me to fully embody the worry and sadness I felt about what was happening in Western North Carolina. And after this leg of the journey, I’d be with my family in Paris, fulfilling a promise I’d made to my daughter when she was a young child: to take her to Paris when she was 16. It would be her first time visiting Europe. This, too, meant responsibility for me, even as it was also a form of privilege.

Still, I didn’t feel so great about being sheltered. I felt ethically compromised to be on the trip of a lifetime while a place and people I loved suffered so immensely, while I watched from afar in almost real time. But wasn’t this also perfectly correct for the way we live now, if an extreme version of such? We are never not tethered to an awareness of the effects of climate change, never not impacted in some way. This episode of uncomfortable dissonance I was feeling? Only one of many more to come.

I did what I could to help the region I love so while I was overseas, but it was not enough, and it will never be enough. I’ll continue doing it, though. There’s no option but to learn how to exist in this reality, and for many of us, this becomes a financial responsibility. It means thinking about my family’s budget and how a portion of it must always account for donations to my fellow humans and creatures experiencing the loss of their homes and ecosystems. I do not have answers. Climate-driven disaster isn’t going to stop happening. The question I want to pose is: What are the new ethics we must learn and adapt for this era? The older, no less essential question behind this is: What responsibility do we have to the places that we visit as well as those we call home—any places we feel connected to? As Jennifer Justus put it in The Grace Before Dinner the other day, touching on the idea of multiple kinds of awe:

The roller coaster of these awes—soaring heights and grand landscapes to threat-based awe and the heavy feelings of helplessness while seeing devastation in North Carolina, Tennessee, South Carolina and Florida, has had me profoundly shook. I know we are all feeling it. The storm(s) and realities of the climate crisis devastating communities where friends and families live and work, the tension of an election that’s about three weeks away, the daily headlines of bombs and deaths in lands thousands of miles away and the everyday challenges of each of our lives feel like an especially pungent monster soup (hat tip to Megan Thee Stallion for the term).

These different types of awe, I’m learning—thanks to Keltner’s book—do have an important commonality. They show our interdependence and how our choices and actions are all part of a larger web. As we’ve watched the images and heard the stories, we’ve wanted to share and give and help. Because we know—despite the efforts of the worst politicians who want to place blame and divide us—we really are all in this together. All of us can relate to, for example, the idea of leaving or losing home and the memories it holds regardless of perceived divisions and voting patterns.

We are better off when we value our interdependence, and we’ll be better off if we acknowledge the way climate crisis touches us all.

Which is why it bothered me, yesterday morning, back at home in Nashville, to see an email subject line that read “Is Tennessee a new climate haven?” My first thought was: Respectfully, folks, enough with the idea of climate havens, okay? We have just seen the fallacy of that in what happened to Western North Carolina (and, mind you, East Tennessee). To focus on the very notion of climate havens is to shirk the demands and responsibilities of interdependence. You can’t haven your way out of what’s happening.

But then I read farther than the headline (which was, I think, a tiny bit clickbaity, but ok ok, maybe subjects lines should be a tiny bit clickbaity by design), and found the sort of reporting I expect and respect from the NashVillager, the daily newsletter from my NPR affiliate, Nashville Public Radio.

Caroline Eggers, an Environmental Reporter for WPLN News, acknowledged immediately that the climate-haven concept is dubious, and linked to this report from Vox: “The shady origins of the climate haven myth.” She went on to note, hopefully, that “Cities, states and industries can take steps to both reduce planet-warming pollution and become more resilient to future disasters,” suggesting that Nashville, and Tennessee, could do so, too, before presenting current facts, i.e., that the powers that be in our state are doing everything but:

The legislature preempted cities from blocking fossil fuel projects in their communities and legally defined gas as “clean energy” — protecting industries that cause the vast majority of climate pollution.

Then, earlier this year, state lawmakers failed to pass a bill to remove regulations on a slice of nature linked to climate resiliency: wetlands.

So much for Tennessee as a “climate haven.”

But what can we do, what can we do? While loving and leading our families, while doing our jobs and serving our callings, while managing the noise and fracture of late-capitalist culture, while fearing and fighting dangerous power-seekers, while bearing witness to unthinkable, unspeakable tragedy the world over?

I’ll point you again to JJ’s lovely piece, where she outlines precisely what she plans to do, among it the following:

-I will do better to take action in the ways I can personally in this climate crisis. As Adrienne Maree Brown says in Emergent Strategy, “small is all.” We can create ripples that matter. And again, I’ll vote for and help elect our best hope currently for clean energy jobs, a clean energy economy and climate action.

- I won’t look away. I won’t numb out. I won’t allow myself to get cynical about where we are. But every now and then, I will try to put down the phone.

I co-sign JJ’s list, and I pledge to donate 10% of the paid subscription-income from FIELD TRIP to orgs helping Western North Carolina/East Tennessee recovery in 2025. If you want to join forces (and feed me encouragement) by becoming a paid subscriber, click here.

I’ll also share something I’m grateful for in this difficult time: the media activists and storytellers and individual artists and business owners doing their part to respond helpfully to crisis conditions and combat social-media-fueled misinformation in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene.

The voices of legacy media, sure. You already know who they are. But I’ve been impressed by the work of some smaller outfits, too (all of which need funding to continue). I’d never heard of Mergoat Magazine before Helene—”an interdisciplinary publication that focuses on the ecological situation in Southern Appalachia and the broader southeastern United States”—but they have been doing excellent work in response to the crisis in Appalachia via social media.

I had heard of Reckon, and am glad to see them publish this piece from Minda Honey, who was herself on a retreat, in the mountains of Western North Carolina, when Helene struck. (Minda has been a part of Field Trip’s Good Southern Women artist Q&A series.)

Individual artists have been doing their part to share vital information and collect and disperse aid and resources. Caroline Williford, Robert Grand, Alexa Rose, Karly Hartzman: These are just a few. Please add your own names to the list in the comments, I would love to know and share with anyone reading this.

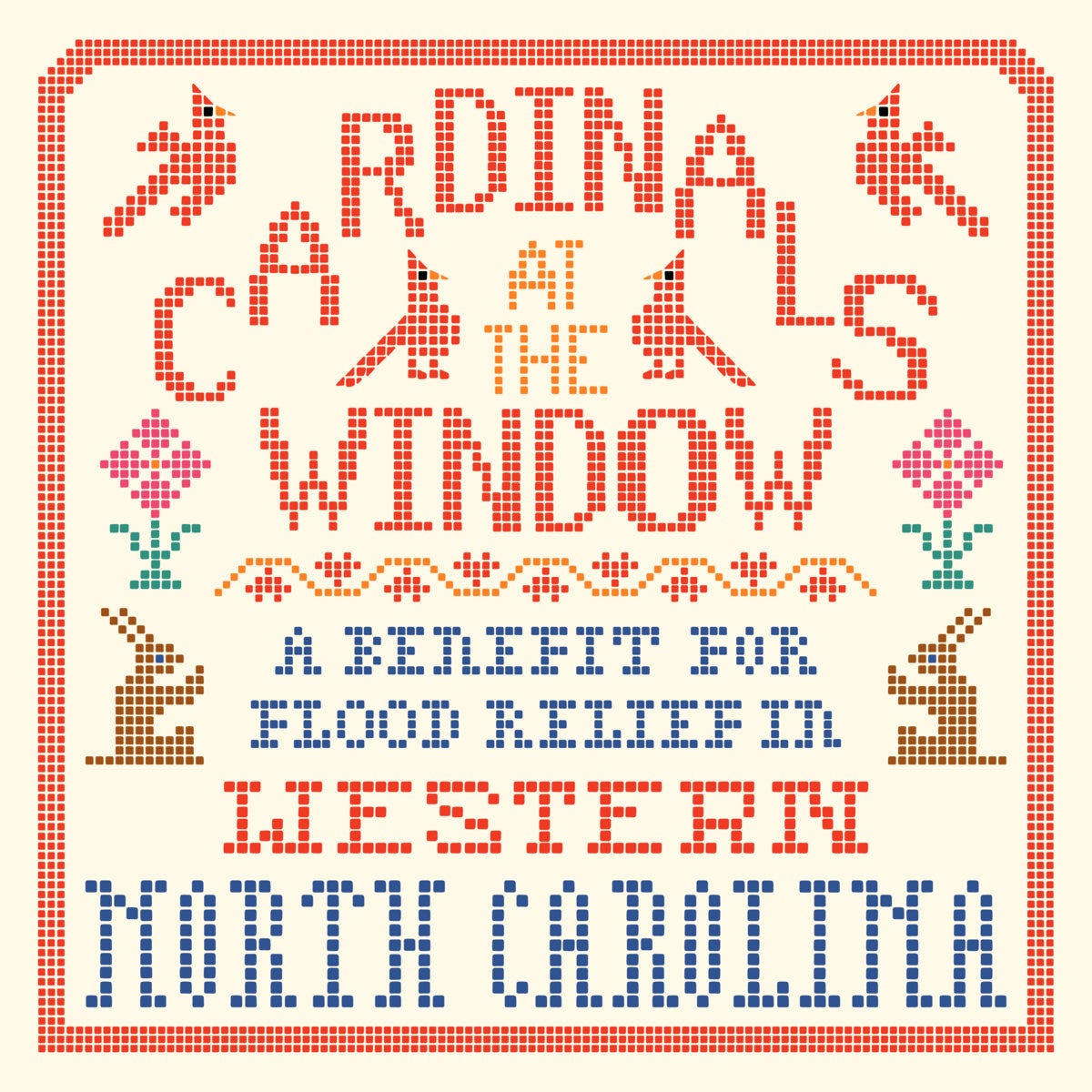

Then there are benefit concerts and the like. There’s Cardinals at the Window, a benefit compilation album featuring 135 unreleased songs by artists such as Waxahatchee, MJ Lenderman, Jason Isbell, Gillian Welch & David Rawlings, and many, many more. (Download it on Bandcamp for a minimum of $10.; 100% of proceeds are split evenly between Community Foundation of Western North Carolina, Rural Organizing and Resilience (ROAR), and BeLoved Asheville.

This action is good to witness, and soothing to the soul to take part in as a consumer, music and arts lover, and/or donor.

I’ve been a fan of East Fork Pottery for years now, not just for their beautiful wares (which…um, don’t get me started), but for their business ethics, and I’ve been impressed by their handling of the moment. Because of East Fork I’d already heard of BeLoved Asheville prior to Helene, and donated a small amount to them through East Fork’s Seconds program. Now BeLovedAsheville is doing the hard work of on-the-ground recovery and is widely recognized as one of the best orgs you can donate your dollars at this time. We need folks like BeLovedAsheville, and we need more companies operating like East Fork does, hand-in-hand with service organizations as a function of regular business.

Buying things may feel like a weak-ass way to respond to disaster, but if there are things you need anyway—holiday presents, anyone?—you could do worse than to spend those dollars with the artists and small business owners who have been impacted by said disaster.

And given that Asheville—indeed, Western North Carolina in general—really is a haven for artists of all kinds, and I am predisposed to care for artists; and given that this little newsletter of mine is, at least in theory, arts-and-culture-and-nature-oriented (I know it wanders a bit, but what good Field Trip doesn’t, I ask you), I’ll close by pointing to the work being done by ArtsAVL, “a designated arts agency for Buncombe County, directly serving artists and arts organizations within the county,” which is partnering with Explore Asheville and other orgs on the Love Asheville From Afar campaign to sustain “the deeply-rooted culture that makes the Asheville area so special.” ArtsAVL is also launching an “AVL emergency relief grant, which provides $500 relief stipends to arts professionals living in the WNC counties impacted by Hurricane Helene.”

SouthArts has also gathered “a list of resources that may be helpful to artists, arts organizations and communities who have been impacted.”

If you love Western North Carolina and the Southern Appalachians like I do, if you value the arts and arts communities, join me in helping them recover in whatever way you can. It matters. It’s only just beginning. Try not to lose sight.

And if you’re like me constitutionally, try not to lose hope. Try not to get too down, worrying about what recovery for the area means in terms of certain developers, and forces of capitalist greed, taking advantage of the situation, as they are prone to do. What will become of the River Arts District in the end? I just can’t let my mind go there too much. I’m trying to shelter myself from that kind of thinking and take action elsewhere.

And! If you…got this far? Wow, thank you. Thank you! I’m seriously grateful for your reading. I deleted two throat-clearing intro grafs about how anxious I felt about writing this one, which is tied to a prevailing sense of “who cares!!!” that skulks around Field Trip lately. But it’s good for me, at least, to do this, so I’ll keep doing it, and hope that your writing is good for you, too.

Also, I think I might start pairing each newsletter with a song or two? Here’s two for today. Let me know if you like them.

Next time: FRANCE!

You have a lot of empathy and compassion and you should absolutely not feel guilty for being on this trip with your daughter. Thank you for sharing these resources.

Thank you for sharing what's in our hearts.